The story of the reconstruction of Cerreto Sannita after the disastrous earthquake of 1688 is a particularly significant one; we are in the late 1600s, but the foresight with which Cerreto Sannita was rebuilt represents an exceptional example not only for the time.

Origin of old Cerreto Sannita

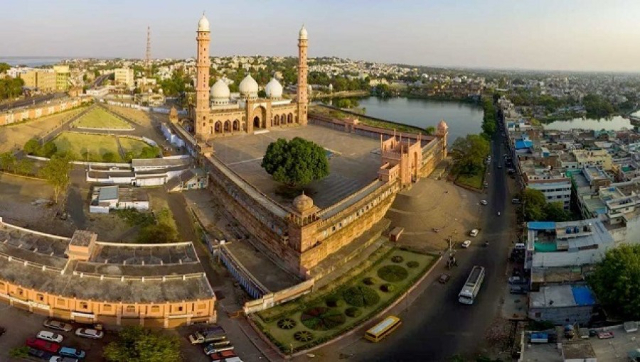

Map of medieval Cerreto Sannita Map of medieval Cerreto Sannita

Medieval Cerreto Sannita was not in the same location as it is today.

Going far back in time, we note that the oldest news of Cerreto refer to what Livy writes about a "Cominium Ocritum," the location of which has been identified in what is now called Monte Cigno.

This mountain is only a few kilometers from present-day Cerreto Sannita; later, perhaps following the Samnite wars, the first nucleus of Samnites who inhabited this village decided to move further down the valley, to the slopes of Mount Coppe; this is the highest mountain overlooking Cerreto Sannita, in the area where the famous castle later arose.

In the Middle Ages the area was then subject to Longobard and later Norman rule. To them we owe the construction of the castle; later the Sanframondi, who were the first feudal lords of Cerreto, donated a wing of the manor to the monastic friars in the first half of the 1200s.

The 1688 earthquake: reconstruction

The tremendous earthquake of 1688 razed the town (the castrum) of Cerreto Sannita entirely to the ground.

While the tragic event brought death and destruction, it also enabled the birth of the new Cerreto Sannita with exceptional innovative features.

But let’s look at the facts.

The feudal lords of the time, the second ever in the history of Cerreto, were the Carafa of Maddaloni. They made a radical decision: to rebuild this town further downstream from the old castrum. Why? The choice was not accidental, but was the result of a very well thought-out decision; in fact, the place where the new Cerreto Sannita was then built was selected after a careful examination of the terrain of the area, making use of the scientific knowledge of the time: some technical experts surveyed the various soils and found that the one where the present Cerreto Sannita stands was the most suitable, the richest in stones; definitely the new place appeared safer than the area of the old Castrum.

The Carafa therefore decided to build the new Cerreto Sannita in the area located by the engineers and imposed their decision on the population of old Cerreto Sannita; as often happens in these tragedies, the earthquake victim population would have preferred not to move, preferring to rebuild on the site of the destroyed city.

It should be noted that not all of old Cerreto Sannita was directly destroyed by the earthquake; many houses collapsed not because of the tremors of the earthquake but because, standing further down the valley, they were knocked down by the collapse of other houses located higher up the hill, which came down, these too, by the earthquake.

The feudal lord wanted to build the new Cerreto Sannita by calling the best technicians of the time and in particular a great architect, Giovan Battista Manni: it was the intention of the enlightened Baroque prince to want to rebuild the center of his county in an innovative way.

The "squared" streets of the new Cerreto Sannita The "squared" streets of the new Cerreto Sannita in an 18th-century partial map of the town

Cerreto Sannita was thus built taking advantage of the most advanced architectural knowledge at the time: the architect Manni therefore drew three parallel roads, one of which took up the route of the road from medieval Cerreto that then reached Telese and then Naples. These roads were then intersected by perpendicular streets.

Another feature was the fact that the same roads would occasionally widen into large squares. These included the largo di San Martino in particular, where the "Collegiata" was made to rise.

This structure consisting of wide, parallel streets and broad was in stark contrast to the structure of the old medieval castrum which had been, like all medieval towns, made up of narrow streets flanked by large, tall buildings. In the event of an earthquake, the new design promised far greater resistance and certainly less damage.

Great care was also taken in the construction of the palaces: houses were built with only one floor above the ground floor. The ground-floor one was built with perimeter walls made from squared stones; the second floor, on the other hand, had walls built from tuffs to give the building less heaviness.

Architecturally, since many of these surveyors, technicians and engineers came from Naples, many of the palaces in the new Cerreto Sannita then reflected, in a small way, the Neapolitan palaces of the Baroque style.

After the reconstruction, the feudal lord had to face a "social" problem: in fact, as mentioned earlier, the few survivors, about 2,000 compared to as many dead, did not want to move, because they intended to rebuild their homes in the same area where the old Cerreto Sannita stood. But the feudal lord also imposed himself violently, going so far as to imprison the most unruly.

One may wonder why the feudal lord was so determined: certainly for an ethical reason, as an enlightened prince who intended to rebuild following new techniques and new ideas; but he was probably also moved by economic interests. In medieval Cerreto Sannita, the economy hinged on the processing of woollen cloth; there were quarters in the town where these cloths were produced, just as there were several dye-works that processed them: these factories were run by ordinary citizens of Cerreto Sannita, one would say today by private individuals, and they stood alongside those run by the feudal lord. Instead, in the new Cerreto, the feudal lord stipulated that the production and subsequent processing of cloth should be managed by him alone!

The same thing happened with the "taverns," a kind of hotel found in the old Cerreto, which were also privately run. In the new one, however, the feudal lord stipulated that the taverns were to be run only by him.

It should be noted that with the reconstruction a large number of workers poured into Cerreto from neighboring towns, Naples, the Neapolitan hinterland, and even Como (the plasterers): this was because local workers and artisans had largely disappeared following the earthquake.

Running taverns and providing lodging for guests therefore proved to be a good business for the enlightened and shrewd principal

TO SEE:

the entire urban center rich in historical-architectural evidence of relevant value;

the Cathedral church;

the Collegiate Church of S. Martino;

the church of S. Gennaro, home of the Museum of Sacred Art;

the church of St. Mary of Constantinople;

the Convent of St. Anthony, home of the Cerreto Ceramics Museum;

remains of ancient Cerreto and then further down the valley the Roman Bridge known as Hannibal’s

Permanent exhibition of ancient and modern ceramics;

Museum of Contemporary Art;

Museum of Sacred Art

Civic and Ceramics Museum of Cerreto.