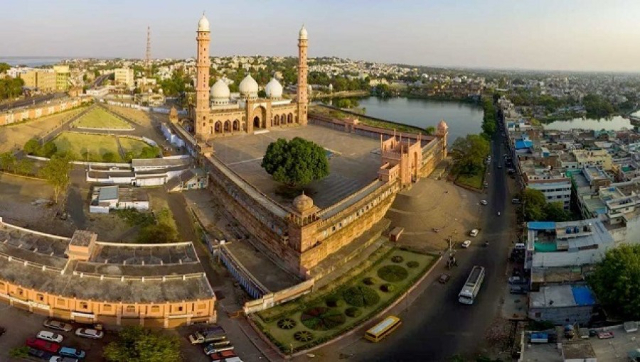

The thermal complex of the Roman age rises on the slopes of Mount Spina to exploit the natural heat sources of the ancient crater of Agnano. The current remains leave little to imagine of the grandeur and magnificence of the original building that was articulated on various floors arranged in terraces on the steep slope of the mountain.

The history of modern thermalism in Agnano starts again, in fact, in the second half of the 19th century, more precisely on September 28th 1870, the day when the draining of the ancient and "pestiferous" Lake Agnano was started. After the unification of Italy, in fact, with a law issued on May 3, 1865, the new unitary state decided to reclaim the lake by granting a Neapolitan entrepreneur, Eng. Martuscelli, to carry out the work at his own expense in exchange for ownership of the reclaimed land and surrounding state lands.When in February 1871 the drainage was completed, to permanently avert the reform of the lake, was built a complex system of tanks and canals, still working today, which allowed to recover 130 hectares of land to agricultural activity. But the reclamation had a secondary and unexpected effect that conditioned the destiny of the plain much more than the recovery of the soils for agriculture. Thanks to the drainage, in fact, to everyone’s great surprise, the great secret of the lake of Agnano was revealed: dozens and dozens of thermal springs, scattered all over the bottom, freed from the waters they had fed for hundreds of years, now gushed and bubbled naturally from the muddy soil at different temperatures forming new pools of water that came out of the ground in large jets.

large jets that made it immediately necessary to build special evacuation channels. Some springs were so abundant that they immediately formed real lakes, such as the extraordinary hot ferruginous spring that gushed from several large springs in the north-western part of the plain.

Nevertheless, no one seemed to grasp, at first, the importance of this discovery and we had to wait more than fifteen years for someone to think of turning so much wealth into something productive. In 1887, in fact, a Hungarian doctor named Giuseppe Schneer, attracted by the fame that Italy enjoyed among foreign intellectuals, went to Naples accompanied by his wife and faithful collaborator Baroness Von Stein Nordein. Among the many excursions he made on that occasion, he went to Agnano, a place that had always been famous in all European countries for the stoves of St. Germano and the naturalistic curiosities such as the phenomenon of the Grotta del Cane (Dog Cave) that so fascinated the travellers on the "grand tour". But what he saw went well beyond his expectations and his scientific curiosity so that he was literally stunned in front of the immense plain recently reclaimed teeming with hot springs of all kinds.