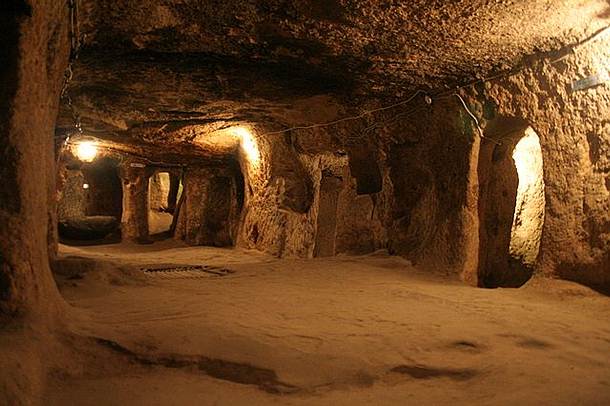

They are carved out of the tuff, the underground cities of Turkey. Derinkuyu, which was opened to the public in 1969, is not an isolated phenomenon. Kaymakli, Ozkonak, Mazikoy and Zelve are the names of other underground settlements in Cappadocia, but it is thought that in the province of Nevsehir alone there are more than 50, some say as many as 200. Derinkuyu, perhaps the largest of all, according to the calculations of the experts reaches with its different levels (at the moment twelve have been recovered) the 100 meters of depth. It is then said that a tunnel of eight kilometers connects Derinkuyu with the other hypogeal settlement of Kaymakli. Cappadocia: a mountainous territory in the center of the Anatolian peninsula, has long been known for its cave dwellings, for its bizarre rock formations pointed like hoods that, seen from above, look like so many natural trulli. A unique spectacle, destination of the colorful hot air balloons that carry tourists from all over the world. Since 1985, this landscape of wild beauty is a UNESCO cultural heritage. It was born from the eruptions of several volcanoes occurred millions of years ago, first of all the imposing Erciyes. These eruption centers, powerful hotbeds in the heart of the Earth, have ceased their surface activities for tens of thousands of years (except for isolated episodes in historical times). Erosion by atmospheric agents has completed the work by working the cooled volcanic flows, sublimating them into dreamlike curvilinear shapes, sculpting into them the clear waves of a vast sea of tuff, the tall sharp peaks silhouetted against the blue sky.\nThe tuff is a fairly "soft" material. It facilitates the work of excavation and also has excellent thermal properties, so the temperature of the chambers carved from the tuff is mild both during the summer heat and during the long, cold winter months. It is clear that these advantages have inspired the construction of livable environments within the rocks. Over the millennia, the caves of Cappadocia have been used as houses, churches, convents, hermitages, cellars, forges, workshops, schools, and today some of them host hotels for tourists who want to spend an exclusive vacation in the nature, far from the crowded centers. Real labyrinths made of tunnels, steep stairs, rooms and niches. In Derinkuyu one would be lost, if arrows and electric light did not appear from time to time. The rooms are mostly empty, devoid of frills and decorations. In some of them are still visible the tools of everyday life such as millstones, workshop ovens, stone wineskins for food preservation. And then there are also traps that had the function of hindering the entry of unwanted people. There are giant boulders of discoidal shape that acted as armored doors, sealing the access to the city at strategic points and protecting it from possible enemy penetration. These discoidal boulders weigh tons and were so built that, once pushed into position to close the entrance, they could not be removed from the outside but only by those who were inside the cave. A more than obvious indication of the primary function of these underground cities, that of safe haven against hostile attacks. The deeper one descends, the more the number of chambers decreases, while their width increases instead.\nThe number of people who could find refuge in Derinkuyu, different opinions circulate. Some speak of 30,000 people, but this really seems like an exaggerated figure. The underground cities were designed to be completely autonomous, so inside there were latrines, cisterns, warehouses, wells, kitchens, schools, churches, and everything that served the life of a community. Particularly in Derinkuyu the natural water supply was provided by an underground river, therefore almost inexhaustible. Inconspicuous openings directly to the outside favored the change of air. And all this means that they were made for the purpose of having to spend long periods down there. Well, the presence of 30,000 people in Derinkuyu’s underground system would soon lead to serious problems of a hygienic nature due to the scarcity of sanitary services; of fast depletion of food supplies due to the narrowness of the storage areas; as well as difficulties caused by the ventilation system which, in the long run, would prove insufficient. A density too high, even for the approximately 400 habitable rooms whose existence has been verified inside the hypogeal city. More realistic seems instead the figure of about 2000 – 4000 inhabitants. The disturbing questions remain: who built these underground cities and for what purpose? From whom or what did they want to protect themselves and their people? The dating conundrum persists. An important clue in aid of archaeologists comes from the Greek historian Xenophon (V-IV century BC), which in his writing "Anabasis" speaks of underground cities of Anatolia inhabited by Phrygians: "The houses were underground, narrow entrance as the opening of a well, widened downward. The entrances for the cattle were dug and the people went down by means of ladders. In the dwellings were goats, sheep, steers, and birds with their offspring." (Xenophon, "Anabasis," book IV, 5.25)\Another passage in the Anabasis (in book I) tells of how the Phrygians, in order to escape the impending arrival of the Persian Cyrus (6th century BC), abandoned their cities and took refuge in the mountains. And it is probable that these populations have already begun some centuries before, to defend themselves from the attacks of the Assyrians, to build the system of underground tunnels. The shelters may have assumed the function of cities even for a fairly long period. A sort of "bunker" of the past, in which people had the possibility to continue their lives in safety, participating in religious services, taking care of the education of their children, organizing assemblies and community festivals.\In the underground city of Derinkuyu tools of Hittite origin have been found. We know that this territory was occupied by the Hittites (2nd millennium BC), but it is possible that the artifacts ended up there even later, at a later time.