The city of Chandigarh is situated at the base of the Shiwalik Range of the Himalayas, at 333m above sea level, approximately 260 km northwest of India’s capital, New Delhi.The city forms the urban core of the “Union Territory of Chandigarh”, which has a total area of 114 sq km. All of the urban and architectural work of Le Corbusier listed in this document is located within Chandigarh’s “Phase One”, an area of approximately 70 sq. km. which can be regarded as the city’s “Historic Core.”The idea of building Chandigarh was conceived soon after India’s independence in 1947, when the tragedy and chaos of Partition, and the loss of its historic capital Lahore, had crippled the state of Punjab. A new city was needed to house innumerable refugees and to provide an administrative seat for the newly formed government of re-defined Punjab. Beginning in early 1951, most of Phase One had been completed by 1965.Unlike the 14 other contemporaneous new Indian towns, Chandigarh was regarded as a unique symbol of the progressive aspirations of the new republic and the ideology of its struggle for independence.

The Chandigarh Project was, at first, assigned to the American planner Albert Mayer, with his associate Matthew Nowicki working out architectural details. Le Corbusier’s association with the city was purely fortuitous, a result of Nowicki’s sudden death in August 1950.Beginning in 1951, he continued to be associated with the city as the principal ‘architectural and planning advisor’ for the till his death in1965. As it turned out, there was none else who could have matched Prime Minister Nehru’s lofty optimism and his progressive, modernist vision for an impoverished, politically unstable, newly independent nation.

The most significant role played by Le Corbusier in Chandigarh was in conceiving the city’s present urban form. It is the well-ordered matrix of his generic ‘neighbourhood unit’ and the hierarchical circulation pattern of his ‘7Vs’ that has given Chandigarh its distinctive character. The Matrix comprises a regular grid of the fast traffic V3 roads which define each neighbourhood unit, the ‘Sector’. The Sector itself was conceived as a self-sufficient and – in a radical departure from other precedents and contemporarous concepts – a completely introverted unit, but was connected with the adjoining ones through its V4 – the shopping street, as well as the bands of open space that cut across in the opposite direction. Day-to-day facilities for shopping, healthcare, recreation and the like were arrayed along the V4 – all on the shady side. The vertical green belts, with the pedestrian V7, contained sites for schools and sports activities.

A city such as described above could be placed almost anywhere. But what distinguishes Corbusier’s design for Chandigarh are the attributes of its response to the setting. The natural edges formed by the hills and the two rivers, the gently sloping plain with groves of mango trees, a stream bed meandering across its length and the existing roads and rail lines – all were given due consideration in the distribution of functions, establishing the hierarchy of the roads and giving the city its ultimate civic form. Connecting the various accents of the city – such as the Capitol (the ‘head’), the City Centre (‘the heart’), the University and the Industrial Area (the two ‘limbs’), etc. and, also scaling its seemingly undifferentiating matrix, were the city’s V2s. Corb’s ‘V2 Capitole’ or Jan Marg (People’s Avenue), was designed as the ceremonial approach to the Capitol. His ‘V2 Station’, the Madhya Marg (Middle Avenue), cut across the city, linking the railway station and the Industrial Area to the University. The third V2, Daksh in Marg (South Avenue) demarcates the first developmental phase of the city.

Le Corbusier’s contribution to regulating the built mass of the new city includes an extensive range of architectural controls covering volumes, façades, textures – especially for the major commercial and civic hubs such as the V2s. Recognizing the crucial role of trees as elements of urban design along, he also devised a comprehensive plantation scheme, specifying the shape of trees for each category of avenues, also keeping in view their potential for cutting off the harsh summer sun. A protected green belt, the ‘Periphery’, which was given a legal backing through a legislative act, was introduced to set limits to the built-mass of the city and as a measure against unsolicited sprawl outside the plan area.

Besides determining the city’s urban form, Le Corbusier, as the “Spiritual Director” of the entire Chandigarh Capitol Project, was also responsible for designing the key ‘Special Areas’ of the city, each of which contains several individual buildings. The most significant of these is the ‘Capitol Parc’ – the ‘head’ and la raison d’être of the entire enterprise. A parallel undertaking – one of almost equal significance as the Capitol, was Le Corbusier’s design of the city’s ‘heart’, the City Centre. In time, the design of the ‘Cultural Complex’ along the ‘Leisure Valley’, including the Government Museum and Art Gallery and the College of Art (L-C’s Centre for Audio-visual Training), as well as some other smaller works (such as the Boat Club and parts of the Sukhna Lake, which essentially were seen as integral parts of the Capitol parc) were also undertaken by him.

The Capitol Parc (Sector 1)

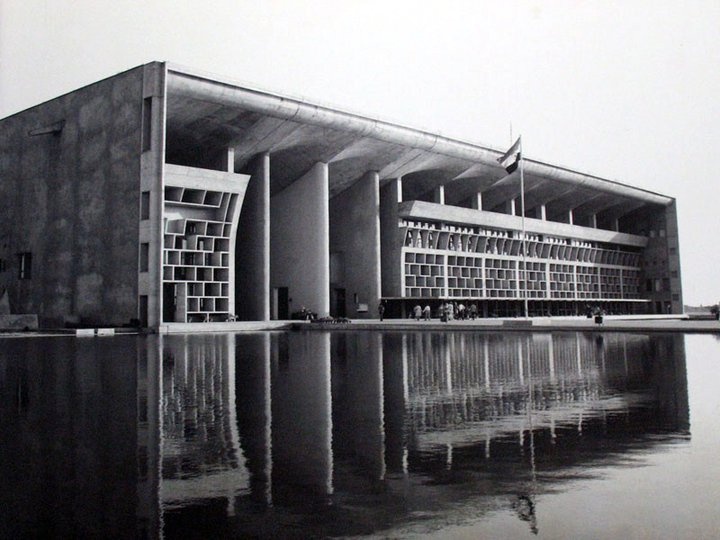

The Capitol Parc is located at the ‘head’ of the city against the backdrop of the Shiwalik Hills. Comprising the Capitol group of buildings, flanked by the ‘Rajendra Park’ and the ‘Sukhna Lake’ on each end, it stretches across the entire width of the city. Symbolizing celebration of democracy in a newly-independent nation-state, the Capitol group of buildings was built to a monumental scale. The group represents Le Corbusier’s largest and most significant constructed architectural creation where the architect put in his heart and soul for over 13 years, painstakingly designing and monitoring the realization of its ingenious layout, its major ‘edifices’, its ‘monuments’ as well as pieces of furniture, lighting fixtures and works of art, including the famed enamel door for the Legislative Assembly, monumental tapestries and low-relief sculptures cast in concrete.

Le Corbusier’s Capitol for Chandigarh comprises four ‘Edifices’ – the High Court, the Legislative Assembly, the Secretariat and the Museum of Knowledge – and six ‘Monuments’, all arranged within a profusely landscaped park-like environment. The layout is based around an invisible geometry of three interlocking squares, their corners and intersection-points marked by ‘Obelisks’. The northern and western edges of the larger 800m-side square define the boundaries of the Capitol, while the two smaller, 400m-side squares determine relative placing of the four ‘Edifices’ and proportions of the spaces in between. Harmonious relationship between various structures is further established though the consistent use of exposed reinforced concrete. The most significant aspect of the layout, however, is the facilitation of uninterrupted pedestrian linkages throughout the complex. A vast concrete esplanade between the High Court and the Assembly thus became the central design feature, along which were arrayed the six ‘Monuments’ and various pools of water. All vehicular circulation was arranged, and dug out where necessary, at 5m below the esplanade. The large quantities of earth thus obtained were used to create ‘artificial hills’, enabling partial enclosure of the Capitol group and emphasizing its careful orientation towards the magnificent view of the hills beyond.

The built ‘Edifices’ – the High Court, the Legislative Assembly, and the Secretariat – represent the three major functions of democracy. Considered as Le Corbusier’s most mature plastic creations, each of these is a masterpiece in itself, representing the adaptation of European Modernism.