The laying of the foundation stone, blessed by Pope Nicholas IV and lowered into the area of the old cathedral church of St. Mary and the capitular church of St. Constantius, dates back to 1290. The initial plan, drawn up by the cathedral’s first architect, who has remained unknown, called for a basilica plan with three naves with six semicircular side chapels on each side, a cross-vaulted transept that did not protrude and a semi-cylindrical apse.

Once the naves and transept were built, when the masonry apparatus had reached the level of the roof impost, a critical moment occurred for the building site, resolved by calling Lorenzo Maitani to Orvieto. Officially justified by the alleged instability of the transept walls, in reality the Sienese architect’s intervention transcended the purely technical sphere and expressed a profound change in taste and artistic program, rooted in the broader context of the city’s political and social history.

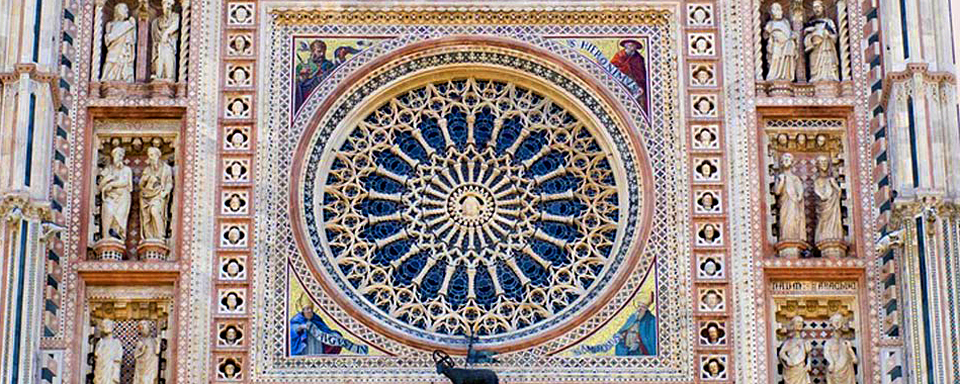

Altering the harmonious unity and continuity of the cathedral’s primitive architecture, Maitani built the unnecessary and "unsightly" supporting structures: buttresses, spurs, rampant arches, and, after focusing his attention on the decoration of the lower part of the facade, he modified its upper part by designing the tricuspidal solution.

the original layout of the cathedral was further modified by the replacement of the semicircular apse with the present square tribune (1328-1335); between 1335 and 1338 the transept was vaulted, and later, in the spaces created between the buttresses and rampant arches, the Corporal Chapel (1350-1356), the new Sacristy (1350-1365) and the New or St. Brizio Chapel (1408-1444) were erected.

After Maitani, who died in 1330, numerous master builders took over the direction of the work:

his son Vitale, Niccolò Nuti (1331-5), Meo Nuti (1337-9), Niccolò again (1345-7), Andrea Pisano (1347-8), Nino Pisano (1349), possibly Matteo di Ugolino da Bologna (1352-6), Andrea di Cecco da Siena (1356-9), Andrea di Cione known as l’Orcagna (1359-80), to whom we owe the rose window, and other Sienese architects, including Antonio Federighi (1451-6), who introduced Renaissance forms with the inclusion of the twelve aediculae on the facade.

In 1422-5 the external staircase was built with red and white marble; about thirty years later the body of the building was completed with the completion of the roof of the tribune and the Chapels.

The 16th-century achievements:

In the sixteenth century, an eagerness for renewal, breaking conformity with the fourteenth-century plan, led to a profound transformation of the cathedral into a Counter-Reformation church, according to the dictates of the Council of Trent and Mannerist taste. The counterfaçade and aisles were decorated with stuccoes, frescoes, and altarpieces, all elements envisaged, together with the marble statues arranged throughout the church, by a unified stylistic and iconographic program elaborated and executed by, among others,: Raffaello da Montelupo, Federico and Taddeo Zuccari, Girolamo Muziano, Simone Mosca and the Orvietans Ippolito Scalza and Cesare Nebbia.

Also in the 1500s the floor was redone and the facade was completed, which two centuries later, was deprived of the oldest mosaics, replaced by copies.